Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Tenants (2023) Film Review

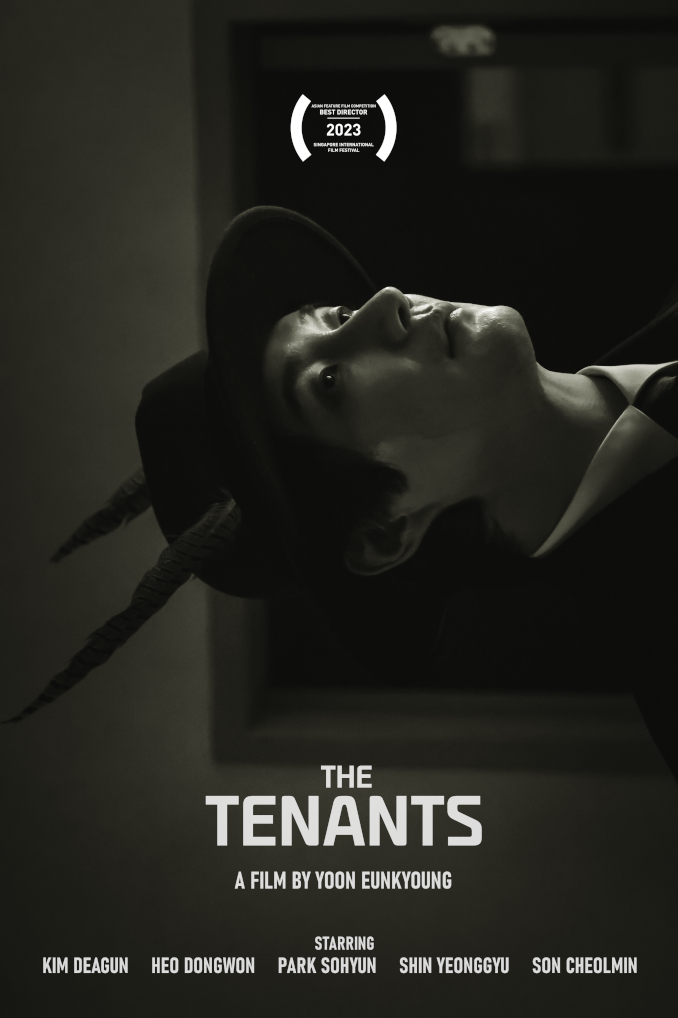

The Tenants

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

If you think the housing crisis is bad in the UK and US, you should check out Seoul, where 6% of households are unable to find accommodation at all and others are paying through the nose for tiny jjokbangs, or ‘piece rooms’ – illegal partitions within other people’s homes or business premises, often with no cooking facilities or basic sanitation. Several films have already been made about this, from Jeon Go-woon’s coruscating drama Microhabitat to Bong Joon Ho’s Oscar-winning black comedy Parasite. Yoon Eun-kyung’s début work, which screened as part of Fantaspoa 2024, is something a little more out of left field.

Set at an unspecified point in the future, when people are living in city domes but the air quality is still terrible, it focuses on Shin-dong (Kim Dae-geon), a lowly office worker who has devoted most of his life to serving a company which produces artificial meat. An asthmatic, he strives to make a good impression so that one day he might get transferred to another city where it’s not so hard to breathe. His situation gets more desperate, however, when his landlord, Mr. Bastard, threatens to evict him. Then he learns that he can secure his tenancy and reduce the burden of his rent by sub-letting part of his apartment to somebody else.

The new tenant (Heo Dong-won) arrives precipitately after the placement of the ad, with his almost silent, smiling, child-like wife (Park So-hyun) in tow. He’s an odd man, very tall and strangely dressed, with two feathers in his hat. He also has a way of resting his face in a smile which somehow gives him an insectoid quality. Shin-dong had been planning to rent out his living room but the couple want the bathroom. At first Shin-dong’s gripes about the arrangement are minor. He’s a very tidy person and they are not; he struggles to sleep and keeps getting disturbed when they go out on late night walks. Then it gets worse. Things move around in his bedroom. He can’t shake the feeling that someone is watching him, and he begins to have disturbing dreams. When he tries to end the arrangement, he finds himself in a much more complicated situation, both socially and legally, than he had anticipated.

With the narrative itself complicated by elements of hallucination which reflect Shin-dong’s deteriorating mental state, the film keeps the reader guessing even as it sets up what might feel like an obvious trap. At a broader level, it reflects on the traps created by an exploitative corporate system in which no amount of effort or self-sacrifice seems to be enough to bring the dream of freedom any closer. That freedom, for Dong-shin, is represented by a postcard of a palm-fringed beach, which may remind viewers of the imagined paradise in Alex Proyas’ Dark City. As in that film, and Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, imagination is perhaps the only real means of escape, and yet, by eagerly engaging with the system, Shin-dong has allowed his perspective to grow narrower and narrower. Now the walls are closing in.

An unusually confident first film, stylishly shot in black and white, The Tenants may explore some familiar ideas but it is very much its own thing. Tight camerawork informed by a keen sense of the absurd gives it a lot of personality, and its bleakness is leavened by humour. It achieves some impressive world-building with its limited locations, while its close focus means that it will still work on a very small screen, should you find yourself with only a cupboard to watch it in.

Reviewed on: 06 May 2024